Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are among the most common infectious diseases in the United States today. More than 20 STIs have now been identified, and they affect more than 13 million men and women in this country each year.

The potential for HIV transmission is enhanced by the presence of STIs, and ulcerative STIs—by virtue of interrupting the body’s most important defense (skin/mucosal membranes)—are of particular concern. Overall, genital ulcer infections appear to increase HIV risk by a factor of 2.7 (approximately 170%). The presence of an ulcerative STD in an HIV-infected individual also appears to increase the likelihood that he or she will transmit HIV to an uninfected sexual partner. Another concern is that HIV infection is associated with non-classical presentations of genital ulcer disease, rendering such infections more difficult to diagnose and treat.

In the United States, most sexually transmitted genital ulcers are caused by genital herpes. Syphilis and chancroid ulcers are less common in the general population. Another STI, lymphogranuloma venereum, is still considered rare in the United States, but it is emerging as a source of concern for clinicians and public health officials alike. To review the standard approaches to diagnosing and treating these four ulcerative STIs—and to discuss some of the latest thinking surrounding these infections—Dr. Susan Blank from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene addressed the PRN membership during a standing-room-only February meeting.

| Lymphogranuloma venereum | Top of page |

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis serovars L1, L2, and L3. C. trachomatis serovar A is responsible for eye disease and serovars B through K are responsible for urogenital disease, most notably chlamydial urethritis and cervicitis.

LGV is endemic is many developing countries, including those in Africa, Southeast Asia, Central and South America, and the Caribbean. Recent outbreaks of LGV among men who have sex with men—most of whom are HIV positive—have been reported in Europe. According to a report published in an October 2004 issue of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 92 cases were documented in the Netherlands between April 2003 and September 2004 (U.S. Centers for Disease Control, 2004). Soon thereafter, a similar report was published by health authorities in Great Britain (Macdonald, 2005).

In recent months, LGV has been reported in the United States, with 12 cases documented nationally (of which seven were documented in New York City). The appearance of this unusual ulcerative STI has been of concern to public health officials, given that an outbreak of LGV—especially if the rates of LGV/HIV coinfection mirror the 75% rates found in Europe—could increase rates of HIV transmission in the United States.

The primary lesion of LGV is a small genital or rectal papule, ulcer, or erosion that appears at the site of inoculation and may or may not be painful. These lesions may be clinically similar to the lesions of genital herpes, primary syphilis, or chancroid. The incubation period from exposure to developing a lesion is approximately three to 30 days.

Figure 1. Inguinal Adenopathy in Secondary Lymphogranuloma Venereum

The primary lesion of LGV is a small genital or rectal papule, ulcer, or erosion that appears at the site of inoculation and may or may not be painful. The secondary stage of LGV can also manifest as an inguinal syndrome, characterized by inguinal or femoral adenopathy that may go on to suppurate and ulcerate (buboes.)

A secondary stage of LGV can occur three to six months after exposure. It can manifest as an anogenitorectal syndrome, characterized by hemorrhagic or non-hemorrhagic proctitis/proctocolitis. Symptoms include purulent, mucous, or bloody anal discharge, rectal pain/spasms, tenesmus, or constipation. The secondary stage of LGV can also manifest as an inguinal syndrome (see Figure 1), characterized by inguinal or femoral adenopathy that may go on to suppurate and ulcerate (buboes). Left untreated, the secondary stage manifestations of LGV can progress to genitorectal fistulae, strictures, or genital elephantiasis.

With respect to the diagnosis of LGV, commercially available tests—including culture, nucleic acid amplification, nucleic acid hybridization, and serologies—can be used to confirm C. trachomatis infection. However, these tests are not specific enough to distinguish between the various chlamydial serovars and therefore cannot be used to confirm a diagnosis of LGV. Definitive testing is available through the CDC, with the help of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s Bureau of Sexually Transmitted Disease Control (BSTDC). Dr. Blank stated that all clinicians with a patient meeting the LGV case definition should call the BSTDC’s LGV desk: 212/788-4423 (see Sidebar).

Because a definitive diagnosis of LGV can take weeks, patients suspected of having LGV infection should be treated presumptively. The recommended treatment is doxycycline, 100mg orally twice a day for 21 days. An alternative treatment involves an erythromycin base, 500 mg orally every other day for 21 days. Some experts recommend azithromycin 1 g every week for three weeks. However, data are not available supporting the efficacy of this option for the treatment of LGV.

To prevent outbreaks of LGV, the NYC DOHMH recommends that sex partners during the six months prior to symptom onset in a possible case also be evaluated, tested for LGV, and treated. Symptomatic sex partners should be treated presumptively for LGV. Asymptomatic sex partners should be given post-exposure prophylaxis consisting of doxycycline 100 mg orally for 21 days. Clinicians requiring assistance in notifying or managing partners are encouraged to contact the BSTDC’s LGV desk.

| Chancroid | Top of page |

Chancroid is caused by the gram-negative Haemophilus ducreyi coccobacillus. The organism is transmitted by direct contact through the skin, most likely through minor abrasions. The incubation period is short: between three to ten days, with symptoms usually occurring by the fifth day. Men typically present with genital ulceration, usually on the prepuce, coronal sulcus, or glans (Figure 2). Women usually present with non-ulcerative symptoms, including vaginal discharge or bleeding and pain while defecating, urinating, or during sex. In women, the ulcers are often subclinical and usually involve either the labia majora or labia minora, but can also occur in the perianal area, the vagina (see Figure 3), or on the cervix.

Figure 2.A Penile Chancroid Lesion

The classic triad of the chancroid ulcer involves a lesion with undermined edges (necrotic base), purulent dirty-gray base, and is associated with moderate to severe pain. Men typically present with genital ulceration, usually on the prepuce, coronal sulcus, or glans.

Source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control Public Health Image Library

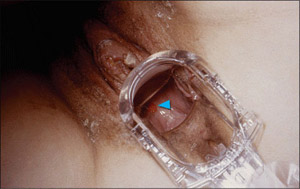

Figure 3. A Vaginal Chancroid Lesion

Note the chancroid ulcer on the posterior vaginal wall in this 25 year old female due to Haemophilus ducreyi bacteria.

Source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control Public Health Image Library

The classic triad of the chancroid ulcer involves a lesion with undermined edges (necrotic base), purulent dirty-gray base, and is associated with moderate to severe pain. Left untreated, approximately 40% of people with chancroid progress from ulceration to adenitis over one to two weeks. “With LGV, patients can feel ill with systemic symptoms,” Dr. Blank said. “With chancroid, we usually don’t see systemic symptoms.”

A definitive diagnosis of chancroid requires identification of H. ducreyi on special culture media that is not widely available from commercial sources. Even with the proper media, the sensitivity is not higher than 80%.

Gram stain can be used to help diagnose chancroid. The classic description of H ducreyi on Gram stain is that of a "school of fish" with small, pleomorphic, gram-negative rods. However, most experts agree that Gram stain has limited utility in diagnosing chancroid. Serologic testing also has limited utility, given its inability to distinguish acute infection from past exposure.

Dr. Blank indicated that newer diagnostic techniques are evolving rapidly. DNA probes and PCR appear promising, with high sensitivity and specificity. However, these assays are not widely available.

Even without conclusive testing, a diagnosis of chancroid is possible. According to the CDC, a probable diagnosis—for both clinical and surveillance purposes—can be made if all of the following criteria are met: a) the patient has one or more painful genital ulcers; b) the patient has no evidence of T. pallidum infection by darkfield examination of ulcer exudate or by a serologic test for syphilis performed at least seven days after onset of ulcers; c) the clinical presentation, appearance of genital ulcers and, if present, regional lymphadenopathy are typical for chancroid; and d) a test for HSV performed on the ulcer exudate is negative. “Ruling out LGV is also important,” Dr. Blank commented.

Treatment is curative and can prevent transmission to others. However, in advanced cases, scarring can result despite successful treatment. Four possible treatment regimens are recommended by the CDC: 1) azithromycin 1 g taken orally in a single dose; 2) ceftriaxone 250 mg administered intramuscularly in a single dose; 2) ciprofloxacin 500 mg taken orally twice a day for three days (although this option is contraindicated in pregnant or lactating women); or 4) erythromycin base 500 mg taken orally three times a day for seven days.

Dr. Blank stressed that follow-up is a very important component of chancroid treatment. Patients should be reexamined three to seven days after initiation of therapy. If treatment is successful, ulcers usually improve symptomatically within three days and objectively within several days after therapy, with larger lesions sometimes taking longer than two weeks to heal. Healing may also be slower for some uncircumcised men who have ulcers under the foreskin. If no clinical improvement is evident, the clinician must consider whether: a) the diagnosis is correct, b) the patient is coinfected with another STI, c) the patient is infected with HIV, d) the treatment was not used as instructed, or e) the H. ducreyi strain causing the infection is resistant to the prescribed antimicrobial.

HIV-infected patients who have chancroid should be monitored closely because, as a group, they are more likely to experience treatment failure and to have ulcers that heal more slowly. HIV-infected patients may require longer courses of therapy than those recommended for HIV-negative patients, and treatment failures can occur with any regimen. Because data are limited concerning the therapeutic efficacy of the recommended ceftriaxone and azithromycin regimens in HIV-infected patients, these regimens should be used for such patients only if follow-up can be ensured. Some specialists suggest using the erythromycin seven-day regimen for treating HIV-infected persons.

| Syphilis | Top of page |

Syphilis is caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, a bacterium that penetrates broken skin or mucous membranes, usually through sexual contact. While morbidity and mortality concerns associated with syphilis are serious in their own right, it is equally important to recognize that the genital and oral chancres that develop during the primary stage of syphilis—much like the other ulcerative STIs reviewed in this article—facilitate the spread and acquisition of HIV infection.

The incubation period, between the time of infection and the onset of symptoms, is approximately three weeks. Syphilis is a disease of stages, beginning with symptoms of primary syphilis. The most significant symptom is the development of a solitary, painless ulcer or chancre at the infection site (Figure 4). Left untreated, a chancre will heal spontaneously. However, two to eight weeks after the chancre heals, symptoms of secondary infection occur. Manifestations of secondary syphilis include diffuse skin rash, keratotic lesions (Figure 5), condyloma latum, and lymphadenopathy. If left untreated, tertiary or late syphilis can develop years after initial infection with T. Pallidum. Symptoms include, but are not limited to, cardiac, ophthalmic, and auditory abnormalities, as well as gummatous lesions.

Figure 4. A Penile Syphilis Chancre

The most significant symptom of primary syphilis is the development of a solitary, painless ulcer or chancre at the infection site.

Source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control Public Health Image Library

Figure 5. Secondary Syphilis

This image shows keratotic lesions on the palms of this patient's hands due to a secondary syphilitic infection.

Source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control Public Health Image Library

Latent stages of asymptomatic infection can be divided into subcategories: syphilis acquired within the preceding year is referred to as early latent syphilis, whereas all other cases are either late latent syphilis or latent syphilis of unknown duration. Treatment for both late latent syphilis and tertiary syphilis theoretically may require a longer duration of therapy because organisms are dividing more slowly; however, the validity of this concept has not been assessed.

Darkfield examinations and direct fluorescent antibody tests of lesion exudate or tissue are the definitive methods for diagnosing early syphilis. A presumptive diagnosis is possible with the use of two types of serologic tests for syphilis.

The first type of testing involves nontreponemal assays that detect the reaction between cardiolipin and nonspecific antibodies produced as a result of T. pallidum infection. Nontreponemal tests include the VDRL and RPR assays. While nontreponemal tests are widely used for syphilis screening, their usefulness is limited by decreased sensitivity in early primary syphilis and during late syphilis.

The second type of testing involves treponemal assays, which detect antibodies to antigenic components of T. pallidum. Treponemal-specific tests include the EIA for anti-treponemal IgG, the T. pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA) test, and the fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption (FTA-abs) test.

As explained by Dr. Blank, it’s important to order both treponemal and nontreponemal tests. “If you screen with only an RPR and the patient is in the early stages of infection, the test may not yet be reactive, much like the window period in HIV,” she said. “If early syphilis is a diagnostic possibility, be sure to order a treponemal test as well, as the seroconversion window period is shorter for a treponemal test such as the FTA-abs. If primary syphilis infection is in the extremely early phase, both the treponemal and nontreponemal tests may be non-reactive. If you suspect primary syphilis, order the lab tests, but treat presumptively.”

It’s important to note that unusual serologic responses have been observed among HIV-infected individuals with syphilis. Most reports have involved serologic titers that were higher than expected, but false-negative serologic test results and delayed appearance of seroreactivity also have been reported. However, aberrant serologic responses are uncommon, and most specialists believe that both treponemal and nontreponemal serologic tests for syphilis can be interpreted in the usual manner for the vast majority of patients who are coinfected with T. pallidum and HIV.

With respect to treatment, parenteral penicillin G has been used effectively for more than 50 years to achieve clinical resolution—whether it’s the resolution of symptoms or the prevention of sexual transmission—and to prevent late-stage manifestations. The CDC-recommended treatments for primary, secondary, latent, tertiary, and neurosyphilis are reviewed in Table 1 (U.S. Centers for Disease Control, 2002).

| Table 1. Recommended Treatments for Syphilis |

| Primary and Secondary Syphilis*:

Benzathine penicillin G (2.4 million units IM in a single dose) |

| Early Latent Syphilis:

Benzathine penicillin G (2.4 million units IM in a single dose) |

| Late Latent Syphilis or Latent Syphilis of Unknown Duration:

Benzathine penicillin G (7.2 million units total, administered as three doses of 2.4 million units IM each at one-week intervals) |

| Tertiary Syphilis: Benzathine penicillin G (7.2 million units total, administered as three doses of 2.4 million units IM each at one-week intervals) |

| Neurosyphilis - Recommended Regimen:

Aqueous crystalline penicillin G (18 to 24 million units per day, administered as 3 to 4 million units IV every 4 hours or continuous infusion, for 10--14 days) |

| Neurosyphilis - Alternative Regimen:

Procaine penicillin (2.4 million units IM once daily), plus Probenecid (500 mg orally four times a day, both for 10--14 days) |

|

*Treatment with benzathine penicillin G, 2.4 million units IM in a single dose is also the recommended dose for HIV-positive patients with primary or secondary syphilis. However, some specialists recommend additional treatments (eg., benzathine penicillin G administered at one-week intervals for 3 weeks, as recommended for late syphilis) in addition to benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM. Source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control, 2002 |

Compared with HIV-negative patients, HIV-positive patients who have early syphilis may be at increased risk for neurologic complications and may have higher rates of treatment failure with currently recommended regimens. However, CDC recommendations state that the magnitude of these risks is likely minimal and points out that no treatment regimens for syphilis have been demonstrated to be more effective in preventing neurosyphilis in HIV-infected patients than the syphilis regimens recommended for HIV-negative patients. Still, some specialists recommend additional treatments (eg., benzathine penicillin G administered once a week for three weeks). Dr. Blank added that Jarisch-Herxheimer reactions are more common in HIV-infected patients receiving treatment for syphilis than in non-HIV-infected patients.

Follow-up testing also remains an essential component of treating primary and secondary syphilis in HIV-positive patients. Such patients should be evaluated clinically and serologically for treatment failure at three, six, nine, 12, and 24 months after therapy.

| Genital Herpes | Top of page |

Genital herpes infection differs from other STDs due to its tendency for spontaneously recurrent lesions. Of the two types of herpes simplex virus (HSV), HSV-2 is the more frequent causes of genital disease. “However,” Dr. Blank cautioned, “HSV-1 is an important cause of genital herpes as well. In medical school, we learned about the waistline delineator: that herpes above the waist is caused by HSV-1 and herpes below the waist is caused by HSV-2. However, we’re seeing an increasing number of genital herpes being caused by HSV-1. In fact, the majority of new genital herpes infections are being caused by HSV-1.”

Primary genital lesions develop between two to 12 days after contact with infected secretions. In males, painful vesicles appear on the glans or penile shaft (Figure 6); in females, they typically occur on the vulva, perineum, buttocks, cervix, or vagina. Perianal and anal HSV infections are also common, particularly in men who have sex with men. Local symptoms include pain/itching, dysuria, proctitis, bilateral tender adenopathy, cervicitis (90% of primary HSV-2 cases), and pharyngitis. Systemic symptoms include fever, headache, malaise, myalgia, urinary retention (10% of primary HSV-2 cases), and aseptic meningitis (11% to 26% of primary HSV-2 cases). “Lesions tend to be smaller than those caused by syphilis and chancroid,” Dr. Blank commented. “There are usually multiple lesions, although they can coalesce. What’s notable with herpes lesions is that the pain is often disproportionately greater than what one might expect, given the clinical findings.”

Figure 6. Primary Vesiculopapular Genital Herpes on the Glans and Penile Shaft

When signs of genital herpes occur, they typically appear as one or more blisters on or around the genitals or rectum. The blisters break, leaving tender ulcers (sores) that may take two to four weeks to heal the first time they occur.

Source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control Public Health Image Library

As for recurrent infections, Dr. Blank pointed out that many individuals experience subclinical primary infection and may not seek out medical care until they have experienced a more noticeable recurrent infection. “As a result,” she said, “clinicians may actually be looking at a recurrent infection that is presenting as a primary infection, because this is the first time the patient has noticed it.” Lesions associated with recurrent infection tend to be unilateral and are generally less severe than those typically seen during primary infection. Recurrences associated with HSV-1 generally occur less than once a year, whereas recurrences associated with HSV-2 can occur approximately four times a year. “Approximately 89% of individuals with HSV-2 experience one or more recurrences during the first year of infection,” Dr. Blank added, “and approximately 35% experience six or more recurrences during the first year of infection.”

In HIV-infected individuals, genital ulcers caused by HSV tend to be more painful and slower to heal. There may also be a larger number of ulcers, as well as larger lesions. Immune-compromised patients may present with herpes ulcers that are unusual in appearance, including hyperkeratotic nodular lesions and denuded lesions. There is also the risk of HSV-related esophagitis, pneumonitis, and cutaneous dissemination. And in HIV-infected individuals with CD4+ counts below 50 cells/mm3, there is an increased risk of HSV shedding from ulcers.

Isolation of HSV in cell culture is the “gold standard” test in patients who present with genital ulcers or other mucocutaneous lesions. The sensitivity of culture declines rapidly as lesions begin to heal, usually within a few days of onset. While antigen detection tests, such as DFA and EIA are widely available, they do not distinguish HSV-1 from HSV-2. PCR assays for HSV-DNA are highly sensitive, but their role in the diagnosis of genital ulcer disease has not been fully elucidated. However, PCR is available in some laboratories and is the test of choice for detecting HSV in spinal fluid for diagnosis of HSV-infection of the central nervous system. Cytologic detection of cellular changes of herpes virus infection is insensitive and nonspecific, both in genital lesions (Tzanck preparation) and cervical Pap smears, and should not be relied on for diagnosis of HSV infection.

As for serologic testing, both type-specific and nonspecific antibodies to HSV develop during the first several weeks following infection and persist indefinitely. Because almost all HSV-2 infections are sexually acquired, type-specific HSV-2 antibody indicates anogenital infection, but the presence of HSV-1 antibody does not distinguish anogenital from orolabial infection. Accurate type-specific assays for HSV antibodies must be based on the HSV-specific glycoprotein G2 for the diagnosis of infection with HSV-2 and glycoprotein G1 for diagnosis of infection with HSV-1. Such assays first became commercially available in 1999, but older—and even some of the more newly-developed—assays that do not accurately distinguish HSV-1 from HSV-2 antibody, despite claims to the contrary, remain on the market. Therefore, the serologic type-specific glycoprotein-based assays should be specifically requested when serology is performed.

Antiviral treatment offers clinical benefits to most symptomatic patients and is the mainstay of management (see Table 2). In addition, counseling regarding the natural history of genital herpes, sexual and perinatal transmission, and methods to reduce transmission is integral to clinical management.

| Table 2. Recommended Treatments for Genital HSV Infection. | ||||

First-Episode HSV Infection:

| Recurrent Symptomatic Episodes:

| Daily Suppressive Therapy:

| Treatment of Episodic HSV Infection in HIV:

| Daily Suppressive Treatment of HSV Infection in HIV:

|

Chronic, suppressive therapy reduces the frequency of genital herpes recurrences by 70% to 80% among patients who have frequent recurrences (i.e., six or more recurrences per year), and many patients report no symptomatic outbreaks. Treatment probably is also effective in patients with less frequent recurrences, although definitive data are lacking. Safety and efficacy have been documented among patients receiving daily therapy with acyclovir for up to six years, and with valacyclovir or famciclovir for at least one year.

Suppressive antiviral therapy reduces asymptomatic viral shedding, which can occur in a sizeable percentage of HSV-2-infected individuals and has been documented to contribute to the ongoing spread of HSV-2. In one pivotal study published in 2004, Dr. Lawrence Corey of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and his colleagues found that daily suppressive therapy with valacyclovir reduced the frequency of HSV-2 viral shedding in infected individuals and reduced the transmission of genital herpes infection among monogamous, heterosexual, HSV-2 serodiscordant couples (Corey, 2004). The acquisition of HSV-2 by susceptible partners was reduced by 48%, and the occurrence of clinical disease among infected partners was reduced by 75%. In turn, not only is there an individual benefit of suppressive antiviral therapy, but also a public health benefit.

| References | Top of page |