A critical aspect of HIV’s evasion of immune and drug suppression is its ability to generate a diverse viral population through high replication rates and high reverse transcriptase mutation rates. Among the broad pool of virus present in an individual with HIV infection are progeny that may survive in the face of pressure exerted from the host as well as non-potent antiretroviral therapy. This same mechanism is responsible for the selection of drug resistance and the need for expanding therapeutic options. Understanding the viral life cycle and its interplay with the immune system is important to finding novel strategies for attack.

The development of CCR5 antagonists is unique in that these drugs are the first available in clinical practice to interact with a component of the human immune system rather than HIV itself. This is one reason that the role of this class of drugs has been less clear than that of reverse transcriptase, protease, and integrase inhibitors, which all target viral products. Another major factor is that the dynamics of viral entry are complex: the virus may evade CCR5 antagonists by use of an alternate coreceptor pathway (CXCR4) for cell entry. This ability of certain strains of HIV to use different coreceptors is referred to as tropism. The tropism of HIV plays an important role in infection, pathogenesis, and its susceptibility to this new class of drugs.

Maraviroc, the first CCR5 antagonist approved by the FDA, has an indication for use in both treatment naïve and experienced adults with CCR5 tropic HIV-1. Reevaluation of studies conducted in treatment naïve HIV-positive individuals that compared maraviroc with efavirenz (both in combination with zidovudine/lamivudine) has allowed extension of this drug’s indication as an alternative first-line therapeutic option. This recent development underscores the importance of understanding HIV tropism and its key role in HIV pathogenesis.

| HIV Tropism and Fusion | Top of page |

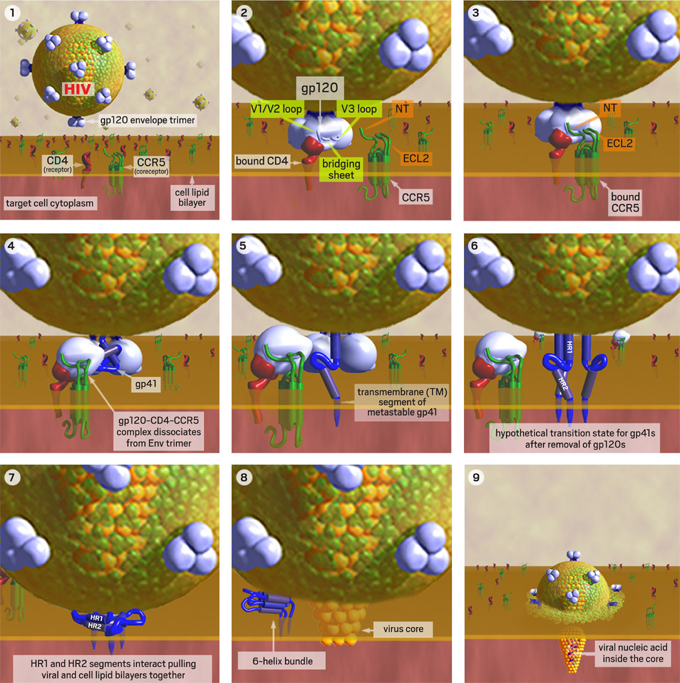

The HIV surface glycoprotein gp160, composed of gp120 and gp41, is the virus’ “key” for entry into the CD4 lymphocyte. The virus’ initial engagement with the CD4 cell is attachment of gp120 to the CD4 molecule on the cell surface (Figure 1).

Figure 1. HIV Binds to a CD4 Cell

1. HIV approaches a human T-cell with CD4 receptors. 2. Binding of gp120 to CD4 exposes its flexible V3 loop, which is the major predictor of viral coreceptor tropism. 3. The exposed V1/V2 and V3-loops interact with the N-terminus (NT) and 2nd extracellular loop (ECL2) of the CCR5 coreceptor. 4. Induced conformational changes allow gp120 to dissociate from gp41. 5. The metastable gp41 rearranges to insert its fusion peptide into the cell membrane. 6. A hypothetical intermediate state with all 3 gp120s removed and the transmembrane (TM) segment of each metastable gp41 inserted into cell membrane. 7. The metastable gp41s rearrange to bring the HR1 and HR2 domains together. These collapsed TM segments are stabilized by helix-helix interactions and bring the virus and cell membranes into close apposition to initiate a fusion pore. 8. Once initiated, the fusion pore rapidly expands pushing the gp41s aside where they rearrange to form a more stable 6-helix bundle. 9. The rapidly expanding fusion pore propels the viral core containing the viral nucleic acid into the target cell cytoplasm.

Images and virus models created by Louis E. Henderson, PhD.

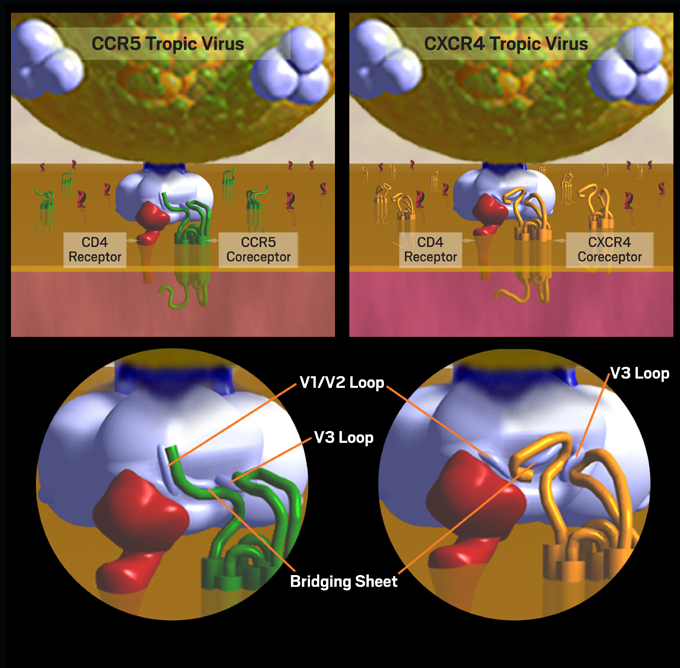

CD4 binding is a necessary first step, but this step alone is not sufficient for HIV entry into a human cell. A second specific attachment to a coreceptor is required. After binding to CD4, gp120 undergoes a conformational change that allows the exposure of its V3 loop segment, which is responsible for co-receptor recognition. The V3 loop of gp120 must then bind to one of two clinically relevant co-receptors on the cell, both of which are 7-transmembrane proteins. These chemokine receptors are known as CCR5 (chemokine [C-C] motif receptor 5) and CXCR4 (CXC chemokine receptor 4).1, 2 These receptors and coreceptors on the human cell have their own inherent functions, but HIV has evolved in such a way that it is able to exploit leukocyte surface markers in order to invade and infect immune cells. The type of coreceptor recognized by gp120 will determine the type of CD4 cell that the virus will be able to infect, also known as the tropism of the virus. Binding to CCR5 is known as CCR5 (or R5) tropism, binding to CXCR4 is known as CXCR4 (or X4) tropism, and the ability to bind to either coreceptor is described as dual tropism (Figure 2). The presence of R5-, X4- and/or dual-tropic virus together in one host is called mixed tropism since assays in current clinical use cannot distinguish truly dual-tropic strains from mixtures of R5- and X4-using populations.3, 4, 5

Figure 2. CCR5 Tropism and CXCR4 Tropism: Dynamics of Cell Entry

HIV tropism (the type of CD4 cell that the virus will be able to infect) is determined by the type of coreceptor recognized by gp120. Binding to CCR5 is known as CCR5 (or R5) tropism, while binding to CXCR4 is known as CXCR4 (or X4) tropism.

Images and virus models created by Louis E. Henderson, PhD.

CD4 is expressed on the surface of T helper cells, regulatory T cells, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. CCR5 is predominantly expressed on T cells (memory and activated CD4 lymphocytes), gut associated lymphoid tissues (GALT), macrophages, dendritic cells, and microglia. CXCR4 is expressed on T cells (naïve and resting CD4 lymphocytes, as well as CD8 cells), B cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils.6, 7

The vast majority (up to 90%) of newly transmitted HIV uses the CCR5 coreceptor. R5 virus, also known as M-tropic virus due to its ability to infect macrophages, is more likely transmitted sexually due to the fact that the virus can infect CCR5-expressing macrophages and dendritic cells on mucous membranes of the genital and gastrointestinal (GALT) tract, which carry HIV to the regional lymph nodes and facilitate contact with and infection of activated T helper cells.8, 9 The natural ligands for CCR5 are RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β, which are responsible for regulation of leukocyte migration and tumor growth.

X4-tropic virus emerges in about 50-60% of infected individuals with an average time to emergence of 5 years.10 X4-tropic virus, also known as T-tropic virus, is associated with more pronounced depletion of CD4 T cells than R5 virus. CXCR4 is expressed on nearly all CD4 T cells whereas only 15-30% express CCR5. Therefore, X4 virus has a wider range of susceptible target cells.11 Unlike CCR5, which may bind a number of ligands and whose ligands may use alternative receptors, CXCR4 has a more exclusive (monogamous) relationship with its natural ligand, stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1). This may have clinical implications on the impact of the development of CXCR4 antagonists to block HIV entry, as SDF-1 is important for maintaining stem cell homeostasis.12

It has been postulated that the relative expression of CCR5 and CXCR4 on cell surfaces may be an important factor in HIV pathogenesis. For example, GALT, which comprises at least 50% of all CD4 lymphocytes, has high expression of CCR5 and this reservoir is currently considered a primary site of initial HIV replication and immune destruction. 13, 14

Coding of the variable region 3 (V3 loop) of gp120 of the HIV envelope is the major genetic determinant associated with CXCR4 coreceptor use. If present, X4-using virus remains as a minor species until conditions change to favor its emergence, such as loss of HIV specific immune inhibition (predominantly CD8 mediated [14]), depletion of CCR5 targets (activated and memory CD4 cells), and the levels of natural ligand which compete for coreceptor binding (high levels of RANTES will suppress HIV through competition for CCR5 binding).10, 15

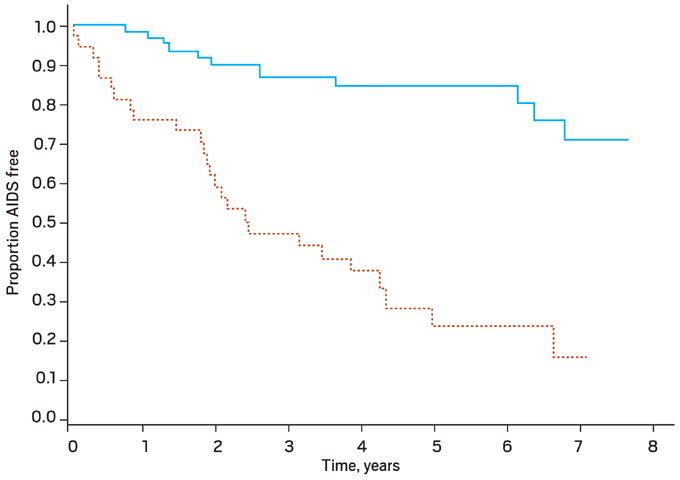

Patients with X4-using virus (X4- or dual/mixed-tropic populations) generally have lower average CD4 counts, more steep CD4 decline over time, and higher viral loads than persons infected with exclusively R5-using virus (Figure 3).15 X4-using virus may be associated with higher rates of bystander (non-infected) cell death or apoptosis than R5-using virus. The presence of X4-using virus (which correlates with the virus’ ability to induce syncitia formation on tumor cell lines [MT2] in vitro) has been associated with more rapid progression of HIV-associated disease, equivalent in magnitude to having a 1 log10 higher viral load.16, 17, 18

Figure 3. Clinical Progression to AIDS: CCR5 versus Dual/Mixed Tropic Virus

Kaplan Meier curves for clinical progression to AIDS (P < .001). CCR5-tropic virus only is denoted by the solid line, and the dual or mixed tropic virus (i.e. CCR5-tropic and CXCR4-tropic) is denoted by the dashed line.

From Daar ES, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:643-649. Reprinted with permission from the University of Chicago Press.16

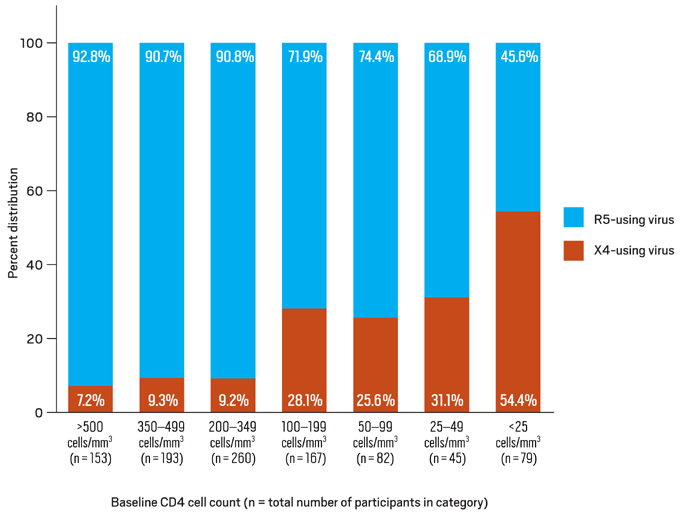

Recent analyses imply that lower CD4 counts and higher viral loads may be seen with dual/mixed tropic virus compared to populations composed of pure R5 or X4 populations; this may be a reflection of the availability of more targets for viral replication.19, 20, 21 Despite earlier reports, it appears that treatment responses to HAART are similar for persons infected with R5-using and X4-using virus, with the exception of regimens that include an R5 antagonist.22 The effect of tropism on rates of disease progression may have implications on the optimal time to initiate antiretroviral therapy. Lower baseline CD4 count has been a strong independent predictor for the presence of X4-using virus (Figure 4).23

Figure 4. Distribution of R5- and X4-using HIV-1 by Baseline CD4 Cell Count

Data derived from Brumme ZL, Goodrich J, Mayer HB, et al.23

Studies have shown that approximately half of all infected individuals have detectable CXCR4 using virus over time. The probability of having X4-using virus is higher among antiretroviral experienced than treatment naïve persons infected with HIV; however, this observation may be largely accounted for by nadir CD4 counts.24 Since the presence of X4-using virus is associated with more rapid CD4 decline, persons infected with X4-using virus would be more likely to be on treatment sooner and have more chance for drug exposure. Another possibility is that antiretroviral drug penetration may differ in viral reservoirs that harbor R5- or X4-using virus.

Despite the association of X4 virus emergence with disease progression, approximately 50% of people who progress to AIDS do so with R5-tropic virus. It has been postulated that R5 virus in these individuals has high affinity for CCR5, binds more efficiently, and is less likely to be inhibited by competition with RANTES or down-regulation of CCR5 expression, resulting in less selective pressure for X4 virus to emerge in this setting.4

The cohort studies reported to date showing an association between low CD4 counts and higher proportions of X4-using virus cannot distinguish whether emergence of X4 is the cause or effect of CD4 decline. It may be that more rapid decline in CD4 counts occurs first, leading to loss of CCR5 targets and/or loss of immune suppression of X4 virus, or that X4-using virus emerges prior to CD4 decline. One group recently reported an analysis from the MACS cohort that studied HIV tropism in 67 persons who had been followed from a known date of seroconversion. Among those subjects with X4-using virus and an identifiable downward inflection point in their CD4 count, X4 virus emerged an average of 10 months prior to the onset of decline.25

In addition, the subjects were divided into quartiles by the time from seroconversion to disease progression from <5 to >11 years. The probability that X4-using virus emerged prior to progression to AIDS was higher in individuals who developed AIDS within 11 years from seroconversion than in those who did not. The median CD4 cell count at X4 emergence was 484 cells/ul. These data suggest that knowledge of the emergence of X4-using virus should prompt earlier initiation of antiretroviral therapy or more aggressive monitoring for disease progression and immunologic impairment.

The feasibility of developing HIV coreceptor antagonists, specifically CCR5 antagonists, was informed by the natural presence of variability in CCR5 expression among human populations. Some individuals, predominantly of northern European heritage, may carry copies of CCR5 genes with a 32-basepair deletion (called Δ-32), which codes for a non-functional protein. It was observed that persons homozygous for Δ-32 (~1% of the Caucasian population) did not express CCR5 and were resistant to infection with R5-tropic virus (which is the vast majority of transmitted HIV). Those persons heterozygous for Δ-32 (approximately 10-15% of the Caucasian population) could become infected with HIV (including R5-tropic virus), but tended to have a more protracted course of disease, and are more likely to have X4-using virus than persons with wild-type CCR5 expression.26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31

CCR5 is more likely to be expressed on TH-1 cytokine producing cells (associated with cell-mediated immune functions). Decreased CCR5 expression may be akin to a shift from TH-1 to TH-2 predominance (associated with humoral/antibody mediated immune function), as observed during natural HIV progression in which there is a decline in cell-mediated immune function relative to humoral immune function. There have been some immunologic effects associated with lack of CCR5 expression including reports of milder course of disease with rheumatoid arthritis and improved kidney transplant survival to increased severity of sarcoidosis and lupus and increased susceptibility to disease due to West Nile Virus.32

The potential importance of coreceptor tropism as a target for HIV treatment was illustrated by a recent case report by Dr. Gero Hutter from Germany of a 40-year-old male with HIV and Acute Myelogenous Leukemia who underwent an allogeneic stem cell transplant from a donor who was CCR5-Δ-32 homozygous. The patient’s HAART was discontinued on the day of transplant. HIV viral load by RNA-PCR and proviral DNA-PCR was monitored. HIV DNA-PCR remained negative for over 600 days post-transplant. On November 13, 2008 the patient was declared “functionally cured.”33 This case may illustrate a potential Achilles’ heel for HIV that may indicate a role for gene therapy in HIV management. However, caution should be exercised before anticipating that the observations from this case report might be readily applicable to a wider population.

| References | Top of page |